Crew Blog | Kaniela Lyman-Mersereau: The Powhatan People

- Posted on 1 May 2016

- In Crew Blogs, Cultural, Newsletter, Teachers

Written by Kaniela Lyman-Mersereau

Written by Kaniela Lyman-MersereauWe awake to gray skies and light wind. Hōkūleʻa sits calmly amidst the ever changing weather, tides, and wind. It is hard not to miss home when you are in cold, moody spring weather. I couldn’t quite peel myself out of bed to join Starr on her early morning run. She came back with exciting photos and stories of revolutionary war reenactments and Cornwallis’ cave. There’s some kind of colonial festival going on in Yorktown this weekend with people dressed like pirates and colonials. Canons and gunshots echo through the air. Exciting stuff for the tourists who dare to brave the cold, gray day.

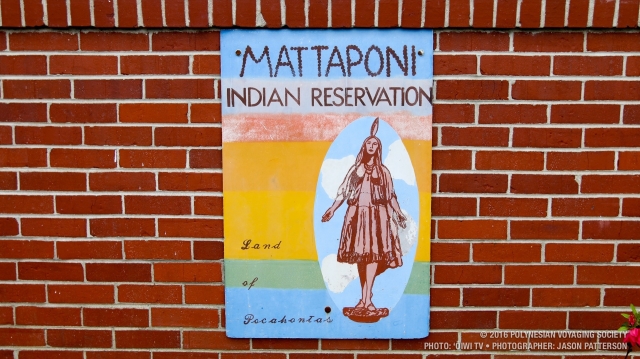

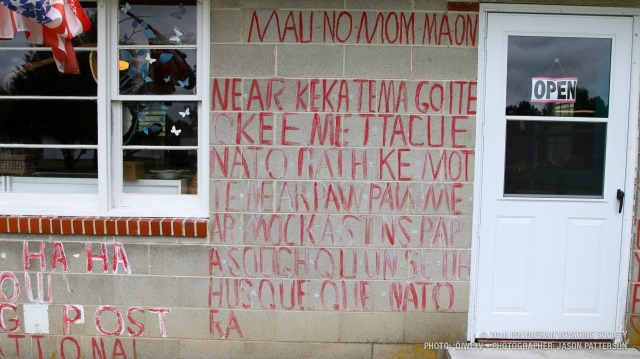

Our plans take us elsewhere to a contrasting scene to meet people who cared deeply for the land and water of this place. Long before tall ships and longboats filled these waterways, the great chief Powhatan’s people moved skillfully with the rivers and tides in dugout canoes and enjoyed the abundance of resources that the land, sea and river offered. We had the privilege to meet two out of 32 Powhatan tribes today at their respective reservations, the Pamunkey and Mattaponi. They are the oldest reservations in North America.

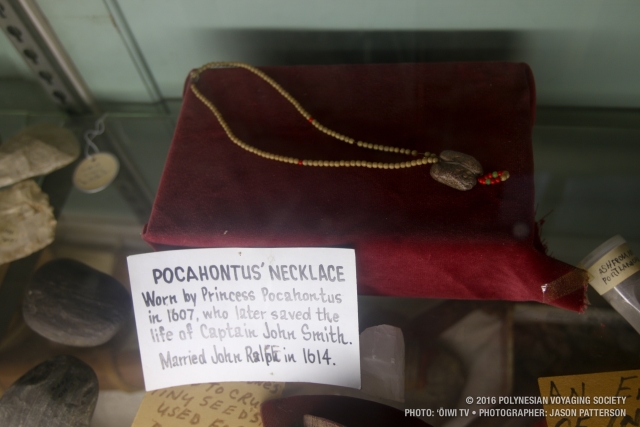

Touring through small museums packed with amazing historical artifacts from Matoaka’s necklace she wore in 1607 to the wooden club meant for John Smith’s execution. Matoaka is Pocahontas’ given name at birth by her father, chief Powhatan. 200 year old dugout canoes, stone tools and tomahawks, countless arrowheads, intricate clay pottery and gourds brought the history of this amazing culture alive. We could not help but feel the connection to home so far away from home. Here is a place that thrived off the water and woods. There was no need to travel from this paradise, but what is it like now?

After being filled with amazing stories about the historic use of certain artifacts to the process of becoming an independent reservation with their own laws to the real story not told about Pocahontas, we learn about a new struggle with regards to the ecology of their river system. Our hosts have figured out a way that was first developed in 1918 to maximize their yield of a fish known as shad and minimize their impact to the populations. They have engineered multiple holding tanks that are used to hatch and take care of young shad until it is safe to return them to the wild. They then put them back in the river system where they will grow in the estuaries then the ocean before coming back to the exact same place they hatched where they can be harvested and ‘milked’ for their eggs once more. This successful process has allowed them to put up to 5 million premature shad back in their river at one time. This process should be taking place right now, but as we enter the hatchery distracted by several large turkey vultures and a bald eagle gliding from tree to tree over a coffee brown river we find a somber sight: No shad to catch, no shad to hatch, no shad to eat.

The elderly man who has had the knowledge of subsistence shad fishing passed down through generations before him says this is the first time he has never had any shad to catch during their normal spawning season. They are over a month late he explains as we learn about the process looking into empty, dry holding tanks. He speaks of various reasons for this change including water temperature and severe weather events, but is not really sure.

As the gray sky becomes darker, we find ourselves at a Pamunkey tribal fish fry event that is usually designated for the running of the shad . The dinner and dessert is delicious and the crew gorge themselves on the amazing buffet, but there are a few dishes missing. The ones that require shad . Sitting, eating, trying not to freeze, we learn about the love for the water that the Pamunkey people have. The chief tells us it is everything to them. From food to recreation, this river is their life. Our host Ashley explains how the peninsula they are on is as close to an island as you can get because of the creek running through it. We share our manaʻo of places we have been along this voyage to places we love back home that share the same love for the water as well as similar struggles in maintaining it. She smiles with her two year old boy in her arms. She is unsure about the shad , but optimistic for the resilience of her people.

We offer our oli mahalo and some makana from home. Moani Heimuli gives a pohaku from her and Hōkūleʻa’s birthplace to the chief in hopes that it will help bring the shad back. The Pamunkey chief accepts it with profound gratitude as the most important gift we gave.

More than Adventure

Beyond a daring expedition, the Worldwide Voyage is quite possibly the most important mission that Hawaiʻi has ever attempted. As people of Oceania, we are leading a campaign that gives voice to our ocean and planet by highlighting innovative solutions practiced by cultures around the planet.

We could not have begun this great journey without your support, nor can we continue to its completion.