Hōkūleʻa Update | December 26-27, 2017

- Posted on 3 Jan 2017

- In Photo Galleries, Updates

On Leg 26, Hōkūleʻa voyages south from Florida to Panama. In this update, science crewmember Anuschka Faucci describes getting settled into her bunk and details some of the marine life she observes in her plankton tows.

December 26

Blog by Anuschka Faucci

It has been over a week now since we have left Miami. Everybody has been adjusting to life on the canoe at their own pace. This is my second deep-sea voyage but my first on Hōkūleʻa. It took me a few days to figure out how to make my bunk comfortable, especially how to have all the things I truly need easily accessible without them getting wet. The bathroom is another one of those things we take for granted at home, but that is different on Hōkūleʻa. It took me a few goes to find out what works best for me, even in rough sees. What has helped throughout this process is the help and advice from the more experienced crewmembers. It has been really great to see this crew, who has known each other just for a few weeks, work together from day one and fine-tune their teamwork over the last few days. We have become a true little family, helping each other out, talking story, singing together after dinner and really getting to know each other.

We are still being towed by Gershon II eastwards into the wind and waves to gain easting. The swells have been up to 15 feet high, making everything a little slower – our progress eastward, walking on the deck, brushing our teeth, cooking, and even typing this blog, as I need to close the box the laptop is in periodically so it wont get drenched in salt water as waves crash over the bow of the canoe.

As a marine biologist one of my roles on board is to record data on water quality and marine life. I am using a multiprobe device to periodically measure temperature, salinity and pH of the water. Since leaving Miami, the water surface temperature has increased from 24 to 27 degrees Celsius. Salinity has mostly been around 34 PSU and pH at around 8, values that are typical for open ocean waters. The salinity was only lower (29 PSU) in Miami at the marina where we were docked, probably due to freshwater input nearby. Tomorrow I will talk a little bit about the marine life we have been seeing floating by or in plankton tows, so stay tuned.

December 27

Blog by Anuschka Faucci

Today has been another beautiful sunny day. We are still heading eastwards against large swells. To kill some time we played a few rounds of a new waʻa balance game some of the crew came up with and are calling “Kūpaʻa.” Its our version of a waʻa makahiki game while weʻre under tow and it was just as entertaining to watch as to participate in and I suspect we will have a few more rounds in the days to come.

As promised yesterday, this blog will feature some marine life we have seen so far. Since we left Miami we have encountered lots of seaweeds and sea grasses floating by. Most of the seaweed consists of Sargassum (in Hawaiʻi called limu kala). Sargassum is a common seaweed worldwide and got its name from a Portuguese word for grape, describing its little grape-like structures. Those grape-like structures keep the seaweed afloat, carrying it along ocean currents. Here in the Caribbean, the main currents will carry floating Sargassum to the Gulf Stream northwards and will eventually end up in a gyre called the Sargassum Sea. The Sargassum Sea got its name from all the Sargassum that accumulates there, building a huge floating habitat for many organisms to live in.

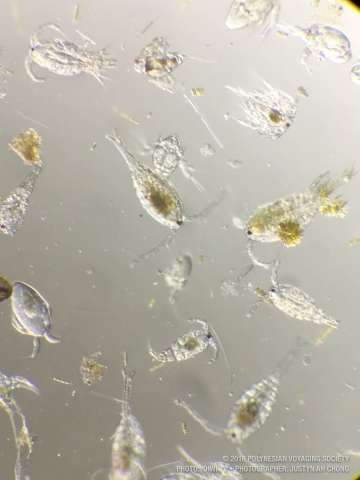

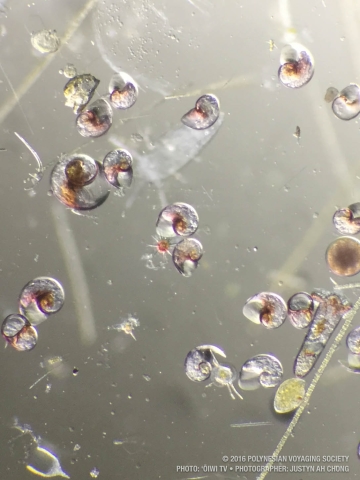

So far I did two plankton tows with the plankton net we have aboard. This plankton net has a very fine mesh size of 80 μm to catch both, the smaller phytoplankton and the larger zooplankton. Phytoplankton is the plant-like photosynthetically active plankton that forms the base of the marine food web and produces at least 50% of oxygen on our planet. Zooplankton includes all planktonic animals, some living their whole lives as drifters in the open ocean and some only during their larval stage while living in coastal areas as adults.

The plankton tow I conducted in the marina while we were docked in Miami included some diatoms (common phytoplankton with silica skeletons), lots of copepods (shrimplike crustaceans), and a few larvae of snails, bivalves, and bristle worms. The plankton tow from the waters South of Cuba resulted in much higher diversity especially of zooplankton, including many different copepods, many larvae of coastal invertebrates such as snails, bivalves, and several different worms, as well as smaller one-celled planktonic organisms such as radiolaria, which look like little spiked balls, foraminifera, dinoflagellates, and many many more. Additionally, there were many puffs and strands of a blue-green alga called Trichodesmium, which can form large accumulations of filamentous strands, forming floating habitats for small organisms, similar to the way Sargassum does for larger ones. The difference in diversity between Miami and South of Cuba probably is due to the difference in salinity. Salinity of open ocean water is around 34-35 PSU, but lower salinities are common in coastal areas with the influx of freshwater. Only few species of plankton tolerate lower concentrations of salinity, and therefore it is no surprise that we found lower plankton diversity in Miami, where we also measured lower salinity.

Iʻm curious to see what we will discover in future plankton tows as we continue to make our way south to Panama.

Hōkūle‘a Homecoming – Save the Date

Sign up for updates and be the first to know as we continue to detail

homecoming festivities that will include multiple events!